Introducing Type-C

A sneak-peek into Type-C, a new programming language I am working on.

Notice

This is a work in progress. The language is not ready yet. I am still working on both the compiler and the VM. I have no guarentee that everything written here will remain the same once the language is released. However, The language design, philosophy, and syntax are pretty much in shape. The standard library and VM instructions are the most likely to change.

What is Type-C

Type-C is my work-in progress programming language which I have been desining for some time now.

Writing a language is something that I have been doing on and off for more than a decade. The challenge is not really to build a language per-se, but to build a language that is useful and that I can use to build other things. For instance, every time I can think of something that could make my language unique, some else is developed which does it better.

I will write about my history with creating languages some other time. At the moment, let’s focus on Type-C.

This language is designed with the following goals in mind:

- Productivity: The language shouldn’t slow you down.

- Type safe: Reduce run time errors.

- Efficiency: The language should be fast. As fast as possible

- Concurrency: The language should have inherent support for concurrency

- FFI: The language should have a good FFI, especially for C

Now that the goals have been set, let’s look at the language itself.

Type-C

Type-C is multi-paradgim language. It is a statically typed language with support for both interface oriented and functional programming. It is designed to be an application-level language, similar to python or modern JavaScript.

- Interface oriented programming: extend interface rather than classes.

- Functional programming: First class functions, closures, variadic types, etc.

- Static and Strong typing: type inference, type annotations, generics, etc.

- Duck typing: Type compatibility is based on the structure of the type rather than the name.

- Concurrency: through processes (agents), not to be confused with OS processes however.

- No Exceptions: Algebraic data types are used for error handling.

- FFI: to C, using shared objects, similar to Lua.

- No RTTI: No run-time type information. Or rather, a very minimal amount of RTTI.

- Embeddable: The language should be embeddable in other applications, such as games.

Type-C will run on top of Type-V, a separate project, which is the Virtual Machine. The current VM implementation is register based, written in C99. The VM itself is very basic at the moment, but as the project gets in shape, more features will be added, most notably, a JIT.

Interface-what?

Interface oriented programming is a paradigm where the focus is on the interfaces between components. The idea is that the interfaces are more important than the implementation. This is in contrast to object oriented programming where the focus is on the objects and their implementation.

You can still create classes in interface oriented programming, but classes are final by nature and cannot extend other classes. Instead, the default inheritance mechanism is through interfaces. An interface is a set of methods that a class must implement. This is similar to the concept of interfaces in Java or Go.

Type-C Encourages the use of composition over inheritance. One of the key advantages of object-oriented programming is code reuse. Inheritance is one way to achieve code reuse. However, inheritance can lead to problems when used inappropriately. Type-C allows inheritance of interfaces, but encourages code-reuse when composition is not possible.

Also interfaces inhenrently provide encapsulation. This is because the implementation of the interface is hidden from the user. The user only sees the interface and not the implementation.

No Exceptions?

Exceptions are a common way to handle errors in many languages. However, exceptions are not always the best way to handle errors. Exceptions are not always recoverable, and they can lead to unexpected behavior. Type-C uses algebraic data types to handle errors.

Here is the tl;dr. Exceptions, as the name suggest, are exceptional cases. But you have them everywhere in your code, then they are no exceptional aren’t they?

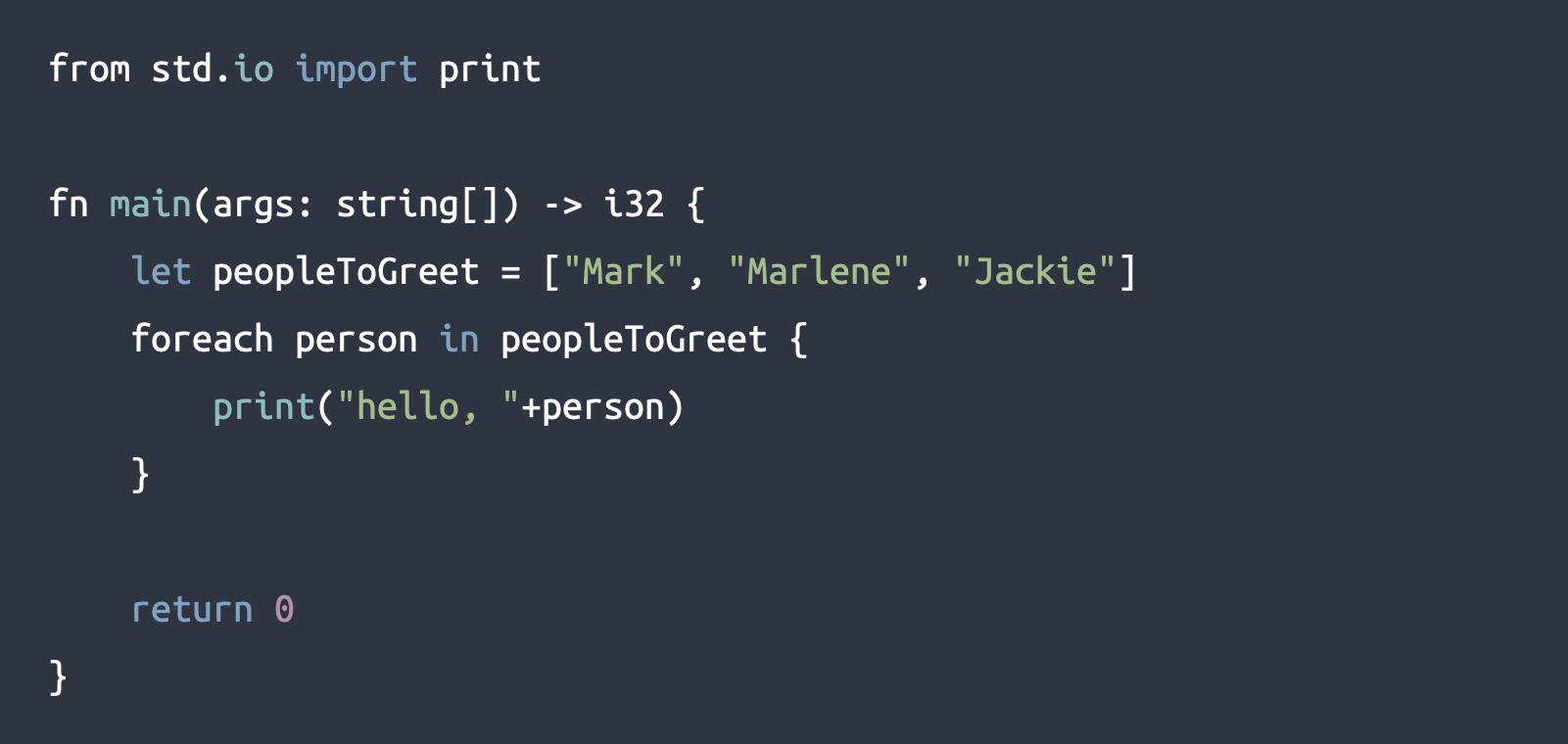

Hello Type-C

Hello World

import std.io

fn main(args: string[] ) -> u32

{

io.print( "Hello, world! ")

return 0

}Fib

fib(x: u32) -> u32 =

match x {

0 => 0,

1 => 1,

_ => fib(n-1) + fib(n-2)

}If you have ligatures enabled, then you have to admit the code looks sexy.

Data Types

// struct

type Point = {

x: u32

y: u32

}

// same as

type Point = struct {

x: u32

y: u32

}

// algebraic type, with a generic-cherry on top

type ServerResponse<T> = variant {

Ok(data: T),

Error(code: u32)

}

let p1: Point = {10, 10} // {x, y}

// types can also be used anonymously

let p2: {x: u32} = p1

fn printPoint(p: {x: u32, y: u32}) -> void {

print("x: ", p.x, " y: ", p.y)

}

printPoint({10, 10})Concurrency

Concurrency is a built-in feature within Type-C, integrated in the form of processes. The model is agent-based, where each process is an agent that can communicate with other agents through messages. Processes are scheduled by the VM, and they are non-blocking. In the following example, type annotations are used for clarity, but they are not required. Type-C type inference can handle process types as well.

import std.io

from std.concurrency import Runnable, Promise

type DownloadInput = variant {

DownloadFile(path: string)

}

type DownloadOutput = variant {

Success(file: File),

Error(error: string)

}

type Downloader = process<DownloaderInput, DownloadOutput>() {

fn receive(req: DownloadInput) {

match req {

DownloadInput.DownloadFile(path) => {

if path.length() == 0 {

return DownloaderOutput.Error("Path cannot be empty")

}

// download the file

return DownloaderOutput.Success(file)

}

}

}

}

/* Spawn process */

let p1: Runnable<DownloaderInput, DownloaderOutput> = spawn new Downloader()

/* Send request */

let promise: Promise<DownloadOutput> = p1.emit(DownloadInput.DownloadFile("/path/to/file"))

promise.then(fn (result: DownloadOutput) {

match result {

DownloadOutput.Success(file) => {

io.print("File 1 downloaded successfully")

},

DownloadOutput.Error(error) => {

io.print("Error downloading file: 1 {}", error)

}

}

// return new promise

return p1.emit(DownloadInput.DownloadFile("/path/to/file2"))

}).then(fn (result: DownloaderOutput) {

match result {

DownloadOutput.Success(file) => {

io.print("File 2 downloaded successfully")

},

DownloadOutput.Error(error) => {

io.print("Error downloading file 2: {}", error)

}

}

p1.terminate()

})FFI

FFI is not really a Type-C feature, but rather a featuer of the VM, called Type-V. The FFI design was massively inspired by Lua. However since Type-C is statically typed, you will need to write both C code and Type-C headers. Here is an example of stdio FFI.

/**

* order is important here, the order in the definition must

* match the order of exported functions in the C code.

*/

extern stdio from "stdio.so" = {

print(number: u32) -> void

}void stdio_print(TypeV_Core *core) {

uint32_t number = typev_api_stack_pop_u32(core);

printf("%d", number);

}

static TypeV_FFIFunc stdio_lib[] = {

(TypeV_FFIFunc)stdio_print, NULL

};

size_t typev_ffi_open(TypeV_Core* core){

return typev_api_register_lib(core, stdio_lib);

}Cool! What’s the state?

Everything is still under-development. The code generator is still being written. The VM needs major features such as GC, improved memory management, etc. So expect any release in mid-2024. I will be posting updates on the language here. So stay tuned.

Additionally, I am writing an official book for Type-C, which will serve as language specification and guide, for both new and experienced programmers. The book will be available for free online, and will be (hopefully) published as a paperback. The book is still in the early stages of development, as I am doing so much work in parallel.

I will keep posting about the language, the virtual machine and the book here, so stay tuned!

Articles written in this blog are my own opinions and do not reflect the views of my employer. Content on this website is original unless mentioned otherwise. Original content is licensed under a CC BY 4.0 Deed. Some of the content might have been preprocessed by AI for clarity and articulation.