Type-C Dev Post 1

In a new series of blog post, I highlight the current status of type-c and the type-v VM. Since I am posting on an infrequent basis, expect the order of these posts to be chaotic.

Type-C

Type-C, does not aim to be a toy language. Even though it is the first large-scale language that I develop (scale is relative), I am trying to make it as efficient as possible. On the road of developments, choices have been made. Some of them are good, some of them are hard to deal with, but each had an impact on the final language. Let’s talk about the some foundations of the language:

- Statically typed language:

Type-C is a statically typed language. Inspired heavily by typescript. The type system is structural, not nominal. This means that types are compatible if their structure is compatible, not if they have the same name.

If it walks like a duck and it quacks like a duck, then it must be a duck.

However, duck typing is fixed to the interface level. Meaning, structs and interfaces both support duck typing, but classes do not. Classes are meant to be final, concrete and well-estbalished entities.

- Interface oriented programming:

Type-C is an interface oriented language. This means that classes cannot extend other classes. Instead, classes can implement interfaces. Interfaces are a set of methods that a class must implement. This is similar to the concept of interfaces in Java or Go. Interface can extend other interfaces, but not classes.

In today’s post, I aim the address how structs are implemented in type-v.

As usual, anything written here might not necessarily end up in the final version of the language.

Problem Definition

We all love javascript objects. They are easy to use, easy to create, and easy to pass around. However, under the hood is a hash function that maps keys to values. This is not very efficient. In order to maintain a minimal level of flexibility and maximum level of efficiency, Type-C uses allows structs to be used with duck typing.

In typescript, we can do the following:

let x = {x: 1, y: 2}

let y = {y: 2, x: 1}

function sumCoords(c: {x: number, y: number}) {

return c.x + c.y

}

sumCoords(x)

sumCoords(y)

// both work just fineWell javascript uses hashmap for fields. So order doesn’t really matter. Type-C aims to be more efficient than that. How can we maintain compability between structs without using a hashmap? The answer is simple, one solution is using offsets.

Type-V Structs

Let’s look at the following example:

fn f() {

let alpha: {x: i32, y: i32} = {y: 1, x: 6}

}

What is important to notice in this example is how the type of alpha is inferred. Even though the type of alpha is not necessarily the value it is being assigned to, it is still compatible with it. This is because the type of alpha {x: i32, y: i32} is structurally compatible with {y: i32, x: i32}.

The way type-c handles this, is by using two different data structures for structs. First being regular struct, second is shadow struct. A shadow struct, is merely a different view of the same structure, it is either the full view or a partial view.

In type-v, each struct has data block, which contains the entire data of the struct. This data block is a contiguous block of memory. Additionally, it also contains an array of offsets. Each offset is the offset of a field in the struct. This is used to access the field of the struct.

A shadow struct, is a struct that has a different view of the same data block. It’s data points to the original data block, but it’s offsets are different.

So think of y: 1, x: 6 as a struct:

tmp1 = {

offsets: [0, 1]

data: [1, 6],

}

a shadow copy with the type {x: i32, y: i32} would be:

tmp_2 = {

offsets: [1, 0]

data: tmp1.data

}

Type-V Structs IR

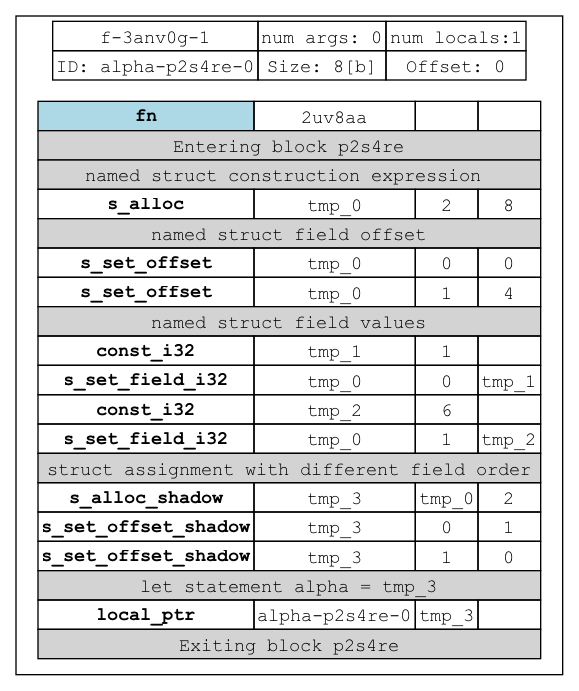

Now let’s have a look at the generated IR for the previous example:

The IR is a bit hard to follow at first, but idea is that, const_[type] such as const_i32 here creates a temporary variable, which will be used a register later on for the actual value.

Let’s look at the instruction we have here

| Instruction | Description | Arg 1 | Arg 2 | Arg 3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

const_i32 |

Creates a temporary variable of type i32 | name | value | |

local_ptr |

Assigned a pointer to a local variable | local target | tmp value | |

s_alloc |

Allocates a struct | Destination | Number of fields | total size in bytes |

s_set_offset |

Sets the offset of a given field index to the given value in the struct | struct | field index | offset value |

s_set_field_[type] |

Sets the value of the given index (through the offset) to the given value | struct | field index | value |

s_alloc_shadow |

Allocates a shadow struct | Original Struct (could also be a shadow) | Destination | Original Struct |

s_set_offset_shadow |

Sets the offset of a given field index (arg1) to the offset of the second given field index in the struct’s original | struct | field index in the shadow struct | field index the original struct |

Now we can interpret the IR as follows:

- Creates a struct and fills it

- Allocates shadow copy of the original struct, with swapped offsets

s_set_offset_shadow struct dest_index src_index will simply perform the following operation:

shadow.offsets[dest_index] = shadow.originalStruct.offsets[src_index]

Let’s try to modify the value of the shadow struct now:

fn f() {

let alpha: {x: i32, y: i32} = {y: 1, x: 6}

alpha.x = 100

}

The new IR looks as follows:

New instructions stores the constant 100 in tmp4 and stores them into alpha struct.

The field index of s_set_field_i32 is 0, but if we go through the offset table.

Since the field 0 offset was swapped with the field 1 offset in the original, the actual offset of the field 0 in the shadow is 4, hence both structs are updated correctly.

Consequences of this design choice:

This design choice has a few consequences:

- If you specify a datatype, and the inferred type, while compatible has a different order, the compiler will generate a shadow struct. This is not necessarily a bad thing, the compiler can be tweeked to re-arrenge the fields in the struct to match the order of the inferred type. However, this is not a priority at the moment. Hence, the compiler will generate a shadow struct, meaning additional instructions will need to be executed, creating slightly more overhead, which scales with the size of the datatype (numer of fields in our struct example).

- Garbage collection is a bit more complicated: If a struct

{x: i32, y: i32}is a shadow of a larger struct{x: i32, y: i32, z: i32[10000]}, the larger struct will remain in memory as long as the shadow struct is alive. The implementation of the GC hasn’t been decided yet, but this is something to keep in mind as well.

Type-C, like any other language will need to rely on developer’s knoweldge of the language to get the most out of it. Blind usage of structures may result in inefficient memory as well as slow code, which could have been easily avoided.

Conclusion

This has been one challenged that I have wanted to address for a while. So far I am pleased with the current solution. Once I get the compiler to 100%, I will start profiling and hopefully compare the performance of type-c against other languages.

Until then, see you in the next artcile.

Articles written in this blog are my own opinions and do not reflect the views of my employer. Content on this website is original unless mentioned otherwise. Original content is licensed under a CC BY 4.0 Deed. Some of the content might have been preprocessed by AI for clarity and articulation.